Fire Extinguishing Museum: "

South of the Aquincum Museum In Obuda while the bases of the transformer of the Electric Co. were being dug up the workers found an antique Roman cellar with caved in ceilings. They found broken bronze pipes and the components of an organ under the ruins. They also found bronze tablets which had data saying that the instrument was given as a present to Aquincum's fire-department, which was lead by Gaius Iulius Viatorinus, in 228 AD.

The organ must have fallen into the cellar in 250 AD, when the building, which eventually burned down, was under siege. Since the cellar was not cleaned out after the fire, the pieces of the organ were left there covered with debris."

In 20 AD, Vetruvius described the operation of a Roman water organ:

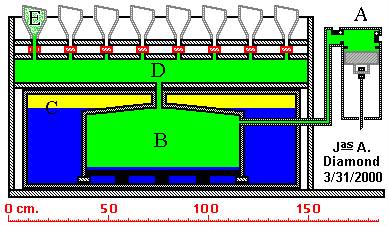

Compressed air (shown in green) is forced by the pump (A) into the air vessel (B). The piston (grey) is shown at the top of its stroke. The air vessel is nearly empty of water (blue) and the surrounding water chest (C) is nearly full. On the downstroke of the piston, water within the water chest flows into the air vessel from beneath, and continues to maintain air pressure within the vessel.

The piston (grey) is shown at the top of its stroke. The air vessel is nearly empty of water (blue) and the surrounding water chest (C) is nearly full. On the downstroke of the piston, water within the water chest flows into the air vessel from beneath, and continues to maintain air pressure within the vessel.

Water can flow into and out of the air vessel because there are spaces between the blocks upon which it sits. On the upstroke of the piston, water is forced back up into the water chest, compressing the air at the top of the water chest (yellow), as well as in the air vessel. (These reservoirs of compressed air may exist for some little time, subject to leaks and to any key being played.) When the piston reaches the top of the cylinder, the pumping cycle is repeated. Valves on the cylinder prevent the escape of air.

The pressure within the air vessel forces air into the wind chest (D), where other valves (shown in red) may be opened or closed by depressing the organ keys. - The Hydraulicus

No comments:

Post a Comment