By Douglas Moreman, Southern University, Baton Rouge, Louisianna

The Battle of Cannae told in many books on military tactics and strategy violates fundamental principles of war and teaches bad lessons to young officers. Hannibal misled, mystified, and surprised his enemy. He created a sequence of real situations and illusions. Some of his deceptions were so good they have been repeated in histories to this day as if they were facts.

I will describe how the historians and books on strategy have erred in their description of the battle. Briefly, I will correct these flaws:

1) the failure to penetrate all of Hannibal's deceptions,

2) the suggestion that one army surrounded and beat to death an army twice its size, and better equipped,

3) the failure to clearly show all four of the major points where Hannibal achieved, by clever plan, overwhelming superiority of numbers,

4) the claim that 8,000 cavalry blocked the retreat of 70,000 infantry,

5) the failure to explain how Hannibal survived what seems to have been an obvious blunder in the disposition of his troops and of his own person,

6) Hannibal had no routes of escape,

7) A successful general sacrifices sizable contingents of his army,

8) There were not multiple paths to success,

9) Hannibal's plan risked his total destruction upon the rapid success of just one contingent of troops.

This Interdisciplinary Middle School Curriculum Unit developed by the Getty Museum includes:

This Interdisciplinary Middle School Curriculum Unit developed by the Getty Museum includes:

"The Romans borrowed parts of their earliest known calendar from the Greeks. The calendar consisted of 10 months in a year of 304 days. The Romans seem to have ignored the remaining 61 days, which fell in the middle of winter. The 10 months were named Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius, Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, and December. The last six names were taken from the words for five, six, seven, eight, nine, and ten. Romulus, the legendary first ruler of Rome, is supposed to have introduced this calendar in the 700's B.C.E.

"The Romans borrowed parts of their earliest known calendar from the Greeks. The calendar consisted of 10 months in a year of 304 days. The Romans seem to have ignored the remaining 61 days, which fell in the middle of winter. The 10 months were named Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius, Quintilis, Sextilis, September, October, November, and December. The last six names were taken from the words for five, six, seven, eight, nine, and ten. Romulus, the legendary first ruler of Rome, is supposed to have introduced this calendar in the 700's B.C.E.

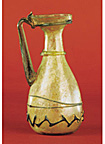

In Natural History XXXVI.192, Pliny the Elder said the invention of glass occurred on the Palestinian coast. He claimed that as natron merchants were sailing from Egypt, they brought their ships to shore at the mouth of the Belus River near Ptolemais. Lacking stones, they used some of their cargo to hold up their cooking pots. The heat from the fire caused the mixture of soda-rich natron and sand to fuse into glass.

In Natural History XXXVI.192, Pliny the Elder said the invention of glass occurred on the Palestinian coast. He claimed that as natron merchants were sailing from Egypt, they brought their ships to shore at the mouth of the Belus River near Ptolemais. Lacking stones, they used some of their cargo to hold up their cooking pots. The heat from the fire caused the mixture of soda-rich natron and sand to fuse into glass.

By ELI EDWARD BURRISS (1931)

By ELI EDWARD BURRISS (1931)

by Jennifer Goodall Powers, SUNY Albany, NY

by Jennifer Goodall Powers, SUNY Albany, NY

I was conducting research on the Mandubians, the tribe that originally inhabited Alesia, today and found an excerpt from Caesar’s commentaries that is missing from MIT’s Internet Classics Archives. I was particularly interested in it because it mentioned the starving Gallic women and children depicted in the recent miniseries.

I was conducting research on the Mandubians, the tribe that originally inhabited Alesia, today and found an excerpt from Caesar’s commentaries that is missing from MIT’s Internet Classics Archives. I was particularly interested in it because it mentioned the starving Gallic women and children depicted in the recent miniseries.

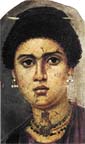

"In 332 BC, Alexander the Great conquered Egypt and for the next three centuries, the Macedonian dynasty of the Ptolemies ruled the country from its capital Alexandria. In 31 BC, the Romans defeated the last Ptolemaic ruler, Queen Cleopatra VII. Egypt fell to Octavian Caesar but Greek remained the official language. In the cross-cultural Roman Egypt that emerged. For some reason Libyans, Romans, Greeks and Jews all developed a taste for mummy portraits. "

"In 332 BC, Alexander the Great conquered Egypt and for the next three centuries, the Macedonian dynasty of the Ptolemies ruled the country from its capital Alexandria. In 31 BC, the Romans defeated the last Ptolemaic ruler, Queen Cleopatra VII. Egypt fell to Octavian Caesar but Greek remained the official language. In the cross-cultural Roman Egypt that emerged. For some reason Libyans, Romans, Greeks and Jews all developed a taste for mummy portraits. "

By Douglas Moreman, Southern University, Baton Rouge, Louisianna

By Douglas Moreman, Southern University, Baton Rouge, Louisianna

By Lesa A. Young

By Lesa A. Young

By Eugene Y. C. Ho, Hong Kong (1960-1997)

By Eugene Y. C. Ho, Hong Kong (1960-1997)

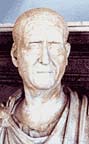

Decius served as consul in every year of his reign and took for himself traditional republican powers, another way to underscore his authority and conservatism. He even tried to revive the long defunct office of censor in 251, purportedly offering it to the future emperor, Valerian. Decius moreover portrayed himself as an activist general and soldier. In addition to leading military campaigns personally, he often directly bestowed honors upon his troops, high and low alike. He also holds the dubious distinction of being the first emperor to have died fighting a foreign army in battle.

Decius served as consul in every year of his reign and took for himself traditional republican powers, another way to underscore his authority and conservatism. He even tried to revive the long defunct office of censor in 251, purportedly offering it to the future emperor, Valerian. Decius moreover portrayed himself as an activist general and soldier. In addition to leading military campaigns personally, he often directly bestowed honors upon his troops, high and low alike. He also holds the dubious distinction of being the first emperor to have died fighting a foreign army in battle.

The toga, the principal outer garment worn by the Romans, is derived by Varro from tegere, because it covered the whole body (v.144, ed. Müller).

The toga, the principal outer garment worn by the Romans, is derived by Varro from tegere, because it covered the whole body (v.144, ed. Müller).

Although the Roman conquest led to the extinction of the Gaulish language 2,000 years ago, a half dozen rare, surviving Gaulish/Latin bilingual inscriptions have enabled scholars to trace the origins of the Celtic language and many other European languages.

Although the Roman conquest led to the extinction of the Gaulish language 2,000 years ago, a half dozen rare, surviving Gaulish/Latin bilingual inscriptions have enabled scholars to trace the origins of the Celtic language and many other European languages.